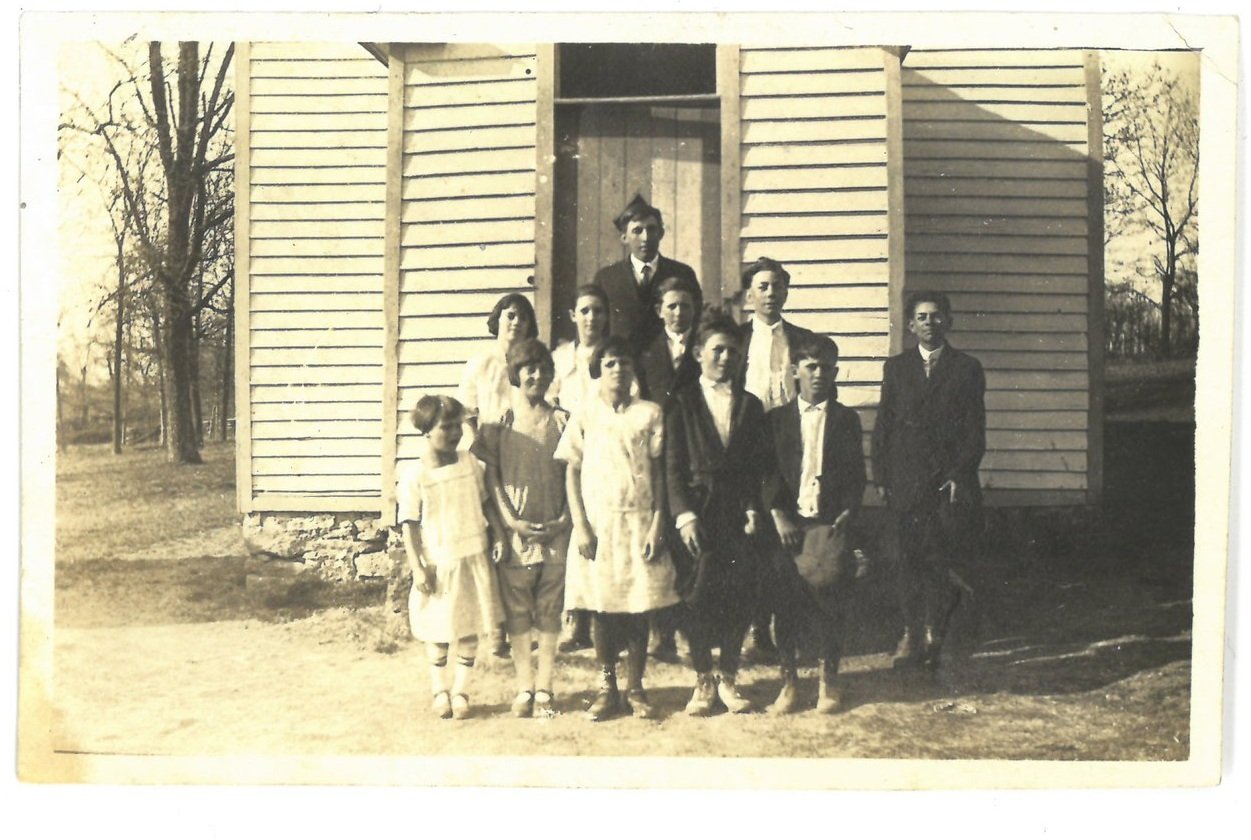

ROSEBUD'S EXCELSIOR-HINTON SCHOOL

A first-hand account by Alice Garrison

ROSEBUD’S EXCELSIOR-HINTON SCHOOL

by Alice Garrison

Excelsior-Hinton School, so named in 1907, at the time I was attending, was equipped with its first crockery water cooler. It was quite an interesting way to get a drink for those of us who had, up until this time, only drunk water from a bucket with a dipper. The water was pumped from the cistern at the back of the schoolhouse and poured into the cooler. There was no ice.

The blackboard consisted of one section of slate on one side and completely across the end of the building. There was another section of blackboard on the other side wall. Often the teacher would put a stenciled border at the top of the blackboard, and the pupils were allowed to color it with colored chalk. It was a special treat to be chosen to color the border.

The only books, which we called “library books”, were in a cabinet about the size of a wardrobe which had glass doors. There was another small cabinet attached to the wall at the front of the room. There were some history and geography books, and the rest were story books. The teacher’s reports at the end of the year to the succeeding teachers often noted that the school needed a phonograph, a globe, dictionaries and more library books. A set of 25 Books of Knowledge were the only reference books available

The only sport equipment was one baseball bat, one ball, and one basketball. The basketball hoops were outside, and boys and girls and teacher played together by boys’ rules. The girls brought pieces of broken dishes from home and had a play area at the edge of the woods at the back of the building. Games such as fox and hounds were played by running into the woods—hounds chasing the foxes.

The highlight of each school year was a pie supper or a box supper. The pupils had a program of plays, songs and recitations after which the decorated boxes were auctioned off to the highest bidder. The young men would bid against one another if they saw that one student was obligated to buy his best girl’s pie. Sometimes a pie would bring as much as $10 which in those times was a lot of money. Then, at the end of the school year, which was usually in the middle of April, each family brought a basket dinner, and, after a program similar to the one at the pie supper, dinner was served on tables outside and everyone shared.

On Friday we would have a spelling bee, an arithmetic match, or a geography match where everyone opened a geography book to the maps, and the teacher would call out a range of mountains, a river or city, and the one who located it first would win. That was an interesting way to learn. There were eight grades in the one room, and when a class was to recite, the teacher called the class and they took the front row of seats and class was conducted. The rest of the pupils were supposed to be studying until their class was called. But, as my brother Floyd used to say, “If you did not learn the work when in one grade, you had the opportunity to learn it by listening to the next class recite.”

The school desks seated two pupils and they shared the shelf for their books and tablets. In the center of the desk was an inkwell, but most of us just kept the ink in the bottle it came in. Sometimes we took the ink home at night so that it would not freeze.

The stove was in the center of the room, and, whenever it was very cold, those whose desks were far from the stove were allowed to move closer to the stove. Of course, sometimes those next to the stove would have been glad to move away to cool off.

The Superintendent of Schools made one visit each school year and always made a talk. One I remember particularly would draw pictures on the blackboard and tell some entertaining stories. We never knew when his visit would be so we were always excited when someone would look out and announce that he was coming across the playground. There was always a flutter while everyone straightened books and papers before he came in.

--Gasconade County Historical Society Newsletter Volume 5, Number 4, Winter 1992